Commentary on A Fuller Picture of Artemisia Gentileschi

A Fuller Picture of Artemisia Gentileschi

Numerous versions of paintings and depictions of The story of Susanna and The Two Elders resulted in different impressions and meanings. Highlighting here is Artemisia Gentileschi's masterpiece. As we read further in the article, it gradually unfolds the reason and story behind each of Artemisia's workpieces.

Artemisia Gentileschi, who was born in Rome in 1593 and painted the scene in 1610 when she was seventeen, presents a completely different Susanna.

According to her testimony, two men emerge from behind a marble balustrade and violently interfere with Susanna's personal hygiene. Her head and torso pull away from the onlookers as she raises a hand in apparent fruitless self-defense toward them. Her face is startlingly hidden by her other hand. Susanna might not want the men to notice her or see her suffering; she could also not want to see the people who are torturing her.

The artwork is exceptionally skilled in terms of conception, execution, and psychological awareness for a girl in her teen years. According to the scholar Mary Garrard, who noted this in a 1989 evaluation titled "Artemisia Gentileschi: The Image of the Female Hero in Italian Baroque Art," the painting represents an innovation in art history because it is the first instance in which sexual predation is depicted from the perspective of the predated. Artemisia established the resistance of women to sexual oppression as an acceptable artistic theme with this painting and numerous later works.

Artemisia was distinguised through her own mark of brushwork and color theory by an Italian art historian Roberto Longhi reluctantly concluded that Artemisa was "the only woman in Italy who ever knew what painting was, both colors, impasto, and other basics."

Revaluing Artemisia's work has been made possible by a renewed understanding of her technical prowess, particularly her mastery of chiaroscuro—an heightened juxtaposition of light and shadow. The artist most commonly associated with the use of chiaroscuro, Caravaggio, whom Artemisia's father knew, and whom she might have met when she was a young adolescent.

A fuller understanding of Artemisia's personal narrative, which was at least as tumultuous as that of Caravaggio, is also related to her resurgence. Artemisia was sexually assaulted by Orazio's companion, the painter Agostino Tassi, in 1611, the same year that she completed her painting "Susanna and the Elders." Her artistic achievements have inevitably, and frequently in a reductionist manner, been seen through the prism of the assault. Her paintings' occasionally violent subjects have been seen as manifestations of wrathful catharsis. Given the persistence of sexual assault against women and the denial of women's stories of it, the fascination with her work on these topics is unsurprising.

However, a number of subsequent academic publications have criticized the depiction of Artemisia as if she were a two-dimensional mythological figure—a victim taking revenge through brushstrokes. As researchers delve further into her personal history, a more nuanced portrait starts to take shape. Additionally, Artemisia's work is becoming more and more well-liked for the skill with which she included aspects of her life—not just sexual misconduct but also parenthood, romantic love, and career aspirations.

Not Artemisia, but her father, who wanted to compel Tassi to marry her, took the choice to publicly accuse Tassi of rape. Artemisia's detailed account of her trauma is part of the official record of the trial, which is kept at the Archivio di Stato in Rome. She alleges that Tassi pulled her inside her bedroom before locking the door.

In her 1989 book, Mary Garrard gave a translation that reads, "He then threw me onto the edge of the bed, forcing me with a hand on my breast, and he positioned a knee between my legs to prevent me from shutting them." Recalling this awful memory is devasting, as well for people who have heard this.

Tassi placed a hand over Artemisia’s mouth to stop her from screaming; she fought back, clawing at his face and hair. In the struggle, she grabbed Tassi’s penis so roughly that she tore his flesh. Afterward, she grabbed a knife from a table drawer and said, “I’d like to kill you with this knife because you have dishonored me.” Tassi opened his coat and taunted her by saying, “Here I am.” Artemisia hurled the knife at him. “He shielded himself,” she tells her interrogator. “Otherwise I would have hurt him and might easily have killed him. Artemisa reflected a memory through The Story of Susanna and Two Elders.

According to Elizabeth Cohen, a historian who has studied the transcripts, the crime of rape was perceived differently in the past than it is today—less as a violent assault against a woman and more as a stain on her family's honor. According to Cohen, depictions of Artemisia as a furious proto-feminist who even in her early works expressed enraged resistance are out of date.

According to Cohen, a woman in the seventeenth century would not have had the same conception of her body as one does today: "Artemisia spoke of her body during the trial, but as the material upon which a socially significant offense had been perpetrated." Artemisia's wrath is expressed in terms of having been dishonored rather than having been assaulted, at least according to the transcript. She claims that "with this nice promise I felt calmer" after Tassi raped her, and she affirms that because she believed his promise to marry her, she agreed to have sex with him on multiple occasions after that. There was a shift of character here. Is rape can be romanticized by saying dishonored after getting through without consent? When consent was given, everything was all calmer and nicer? This cannot be a joke. Assured by words as the concept of marriage was promised, a part of her liked what happened after all or there was just a brink of accepting things just because here I am?

It would be unimaginable in a rape trial today for someone to attempt to force Tassi into keeping his promise to marry Artemisia, as Orazio did. The majority of Artemisia's testimony followed the rules; either she knew what to say or had been told what to say in order to satisfy the requirements for conviction. She was required, like other unmarried accusations of rapists, to submit to a midwife's examination to show that she was no longer a virgin. During the period, suspected victims were subjected to a type of torture to ensure that rape charges were truthful: cables were wrapped around their hands and tightened like thumbscrews. She said it again as the cables were pulled tight, "It is true, it is real, it is true." There was a further investigation after Artemisia have declared the incident of rape, she was not believed at the full extent as she was sketchy about her morals.

Tassi was found guilty but he was sentenced only to a brief period of exile, which he ignored. He did not have to marry Artemisia—it emerged in the courtroom that he had already married someone else. Is taking honor from women some piece of cake being shared with anyone at a birthday party? Is it making you more of a man?

Artemisia Tassi was married to Pierantonio Stiattesi, a struggling artist in Florence, during the course of her father's rape trial. After being married for about ten years, Artemisia reportedly found her husband to be somewhat of a nonentity.

Reclaiming power In 1616, Artemisia de Medici was admitted to the Accademia delle Arti del Disegno. She made her first iteration of Judith beheading Holofernes, now in Naples. Treves: "Artemisia is subverting a well-known traditional subject and empowering the women."

Artemisia bore five children, between the years of 1613 and 1618, making her execution of large-scale paintings during that period all the more impressive. Three of her children died in infancy; another died before the age of five. Only her daughter, Prudenzia, born in 1617, lived into adulthood. Such repeated maternal loss—and the risk that successive pregnancies then posed to a woman’s life—is unimaginable today.

The less dramatic and less well-documented account of what came next has unavoidably been overshadowed by the upheaval of Artemisia's early life and the amazing remnants of it. But given the remarkable nature of her later career, it is safe to infer that Artemisia's experience with being raped had less of an impact on her sense of self than some of her contemporary supporters have claimed. She quickly rose to prominence as one of the most accomplished artists of her era and maintained it for decades; despite frequently being short on money, she never ceased hustling for commissions. (She made this claim that her work embodied the "spirit of Caesar" in order to defend the high cost of a painting.) Despite her fame, Artemisia hardly ever painted for public settings.

Artemisia moved back to Rome after spending half a decade in Florence. According to the city's 1624 census report, she and her husband may have already separated and she was now supporting herself. Artemisia went to Venice, seeking fresh patronage. In 1630, she settled in Naples. She received commissions from, among others, the Infanta María of Spain, who was spending time in the city. Artemisia cultivated such ladies of the court with gifts of beautiful gloves, which she had sent from Rome. Naples became her base for much of the rest of her life, although she disliked the city, which was crowded, poor, and violent.

Her paintings entered the collections of some of Europe's most important monarchs and duchesses. Artemisia is celebrated less for her handling of private trauma than for her adept management of public persona. She was reputed to have been buried in the city’s Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini, her grave marked by a stone inscribed, simply, “heic artimisia”: “Here lies Artemisia.” But any such stone had disappeared by the time the information was written down, in 1812, by the Italian historian Alessandro da Morrona, and the church was destroyed in the twentieth century.

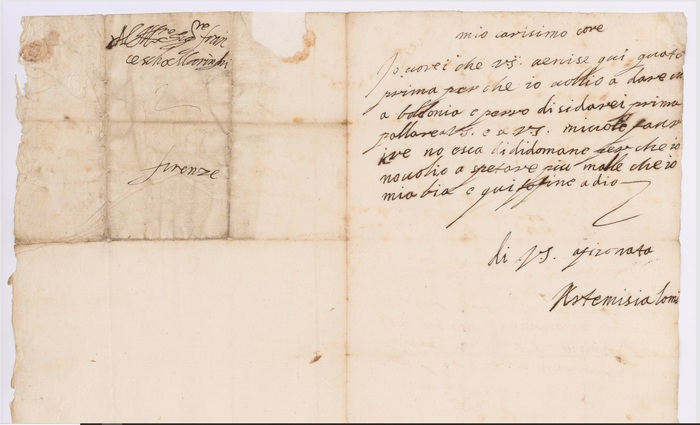

Artemisia Gentileschi had a torrid affair with a Florentine nobleman, Francesco Maria Maringhi. Her letters reveal a passionate, adventurous and even libertine way of life. Recent research has complicated the understanding of Artemisia's moral character.

The interpretation of Artemisia's moral nature has also been altered by recent studies, making her less stereotypically heroic. A collection of letters written by Artemisia, some of which were sent to Francesco Maria Maringhi, a Florentine aristocrat, were found in the Frescobaldis banking dynasty's archive in 2011, by the art historian Francesco Solinas. She had a passionate affair with Maringhi while she was in her mid-twenties and five years into her marriage, it found out.

In the exhibition booklet for the National Gallery, Solinas says that a few of the letters "suggest a passionate, adventurous and even libertine manner of life." Maringhi is referred to as "my dearest heart" by Artemisia in one letter, while in another, she reprimands him for just writing two lines to her, saying that "if you loved me, they would have gone on forever." She makes reference to a self-portrait that Maringhi owns in a third and forbids him from masturbating in front of it. (Unfortunately, the precise portrait is not known.) She saltily expresses her relief that he has only taken his "right hand, envied by me so much for it owns something which I cannot possess myself" as a lover in the same letter.

Artemisia's fame in feminist circles started with the dissemination of her bloodiest and most distressing images. Her variations on the theme of the murderous Judith remain irresistible iconography. Solinas describes Artemisia as "extraordinarily courageous, manifestly unscrupulous, opportunistic and ambitious."

However, in recent years, one of Artemisia's more subdued works has captured the interest of her scholarly fans. Artemisia made a trip to England in her late sixteen years, where her father had moved into a position as a court painter. There, she created several pieces that are now part of the Royal Collection, including "Self-Portrait as the Allegory of Painting," also called "La Pittura." Typically, the metaphorical figure in these paintings is a female. The woman in Artemisia's interpretation, which will be displayed prominently in the National Gallery exhibition, has thick, messy hair and full cheeks. A brown apron is knotted around her waist, and the dress' billowing green silk sleeves extend over her elbows.

The figure is looking at a prepared canvas with a raised brush in one hand and a palette in the other, as opposed to looking out of the frame as is customary with self-portraits. She sags forward, not gracefully, but with the assurance of a skilled craftsperson. This ingenious visual double, in which Artemisia mixed a realistic image of herself at work with an allegorical portrayal of the art form that she so eagerly and successfully pursued, has been noted by experts as something that no male artist could have done. This is the modern-day Artemisia: accomplished, creative, and happily immersed in her line of work.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/10/05/a-fuller-picture-of-artemisia-gentileschi

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/10/05/a-fuller-picture-of-artemisia-gentileschi

Comments

Post a Comment